Introduction

Traditional law and economics is built on the assumption of rational actors who consistently make decisions that maximize their utility. This framework has provided powerful insights into how legal rules influence economic behavior. However, behavioral economics challenges this assumption by demonstrating that individuals frequently deviate from rationality due to cognitive biases, bounded rationality, and heuristics. When applied to law, these insights reshape how we understand compliance, regulation, and the overall effectiveness of legal systems.

This article explores the intersection of behavioral economics and law, highlighting how limits of rationality affect legal outcomes. It examines key behavioral biases, their implications for legal design, and the challenges of integrating behavioral insights into legal systems.

Rational Choice vs. Behavioral Insights

- The Rational Actor Model

Classical economic analysis assumes that individuals act rationally, weighing costs and benefits before making decisions. Legal rules are therefore designed to influence behavior by altering incentives—such as fines for speeding or tax benefits for investments. - Behavioral Challenges

Behavioral economics shows that real-world decision-making often diverges from rational models. People exhibit systematic biases, rely on mental shortcuts, and are influenced by framing, context, and emotions. These deviations have significant implications for law, as legal actors—including citizens, firms, judges, and regulators—are subject to the same cognitive limitations.

Key Behavioral Biases in Legal Contexts

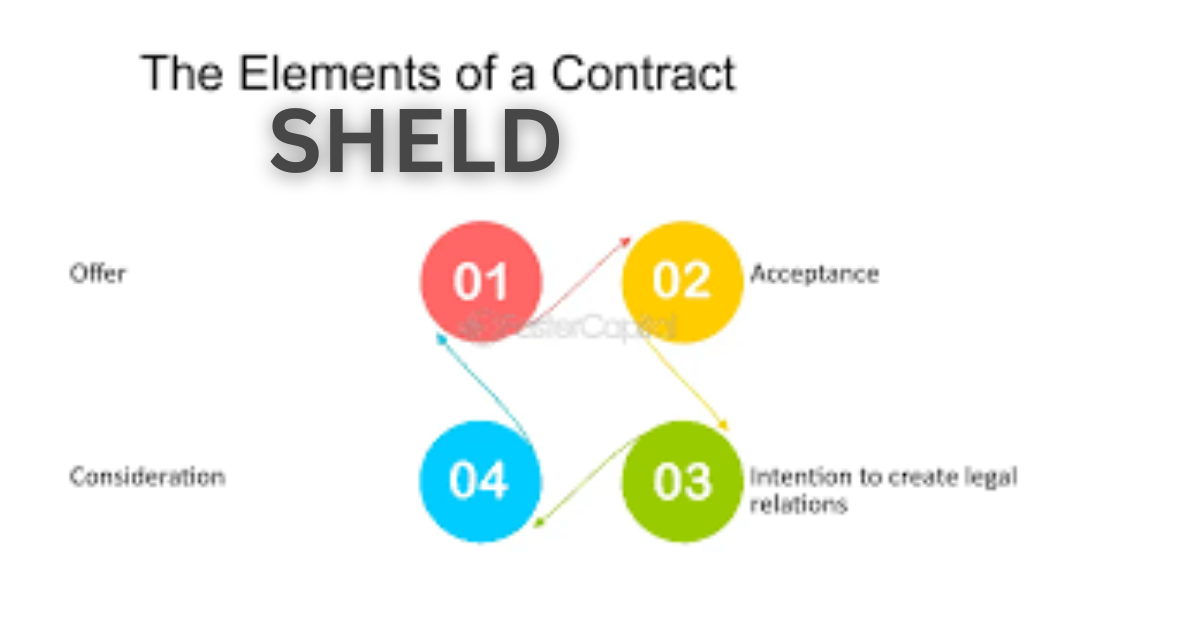

- Bounded Rationality

Individuals have limited information, time, and cognitive processing capacity. Legal systems that assume perfect rationality may overestimate individuals’ ability to understand complex regulations or contracts. For example, consumers often sign lengthy agreements without reading them fully, undermining the effectiveness of disclosure requirements. - Overconfidence Bias

People frequently overestimate their abilities or underestimate risks. Drivers may believe they are less likely to cause accidents, which can reduce the deterrent effect of traffic laws. Similarly, businesses may underestimate the likelihood of regulatory enforcement, leading to non-compliance. - Loss Aversion

Behavioral research shows that individuals fear losses more than they value equivalent gains. This has implications for legal incentives. For instance, framing penalties as losses (fines) rather than gains forgone (discounts) tends to have a stronger deterrent effect. - Status Quo Bias and Inertia

People often stick with default options rather than making active choices. Legal systems exploit this bias through default rules, such as automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans. In areas like organ donation, shifting from opt-in to opt-out systems significantly increases participation rates. - Framing Effects

The way information is presented influences decisions. For example, crime statistics framed in terms of “rising threats” may elicit harsher sentencing preferences compared to the same data presented as “declining trends.” - Availability Heuristic

Individuals assess risks based on easily recalled events. After widely publicized accidents, people may overestimate risks, leading to demands for stricter regulation even if overall safety has improved.

Behavioral Law and Legal Design

- Disclosure Rules

Traditional law relies heavily on disclosure to inform decision-making. However, behavioral evidence suggests that consumers often ignore or misunderstand disclosures. Simplified, standardized, and prominently displayed information is more effective than lengthy, technical documents. - Default Rules

Given the power of status quo bias, default rules play a critical role. For example, defaulting employees into retirement savings plans dramatically increases participation, even when opt-out options remain available. - Nudges and Choice Architecture

Behavioral law emphasizes subtle interventions—or “nudges”—that steer individuals toward beneficial choices without restricting freedom. Examples include calorie labeling on menus, simplified tax forms, and reminders for court appearances. - Penalty Design

Understanding loss aversion helps lawmakers design more effective penalties. Penalties framed as losses tend to deter undesirable behavior more strongly than equivalent rewards for compliance.

Applications in Specific Legal Domains

- Consumer Protection

Behavioral insights reveal why consumers often make poor financial decisions, such as overborrowing on credit cards. Laws that cap interest rates, simplify contracts, or mandate cooling-off periods help mitigate irrational decision-making. - Environmental Law

Behavioral tools can increase compliance with environmental regulations. For instance, framing energy usage reports in terms of social comparison (e.g., “you use more electricity than your neighbors”) has been shown to reduce consumption. - Criminal Law

Deterrence models assume rational calculation, but behavioral research shows that criminals may overweight immediate rewards and underweight long-term consequences. Policies that increase the certainty of detection (e.g., visible policing) may be more effective than increasing penalties. - Tax Compliance

Behavioral evidence suggests that emphasizing social norms and fairness can increase tax compliance. Letters reminding taxpayers that “most people pay their taxes on time” have proven more effective than threats of audits.

Challenges and Criticisms

- Paternalism Concerns

Critics argue that behavioral interventions risk excessive paternalism, undermining individual autonomy. The balance between nudging and preserving freedom of choice remains a contentious issue. - Unintended Consequences

Behavioral interventions can backfire. For instance, excessive reliance on defaults may lead to complacency, where individuals accept suboptimal arrangements without scrutiny. - Scalability and Context

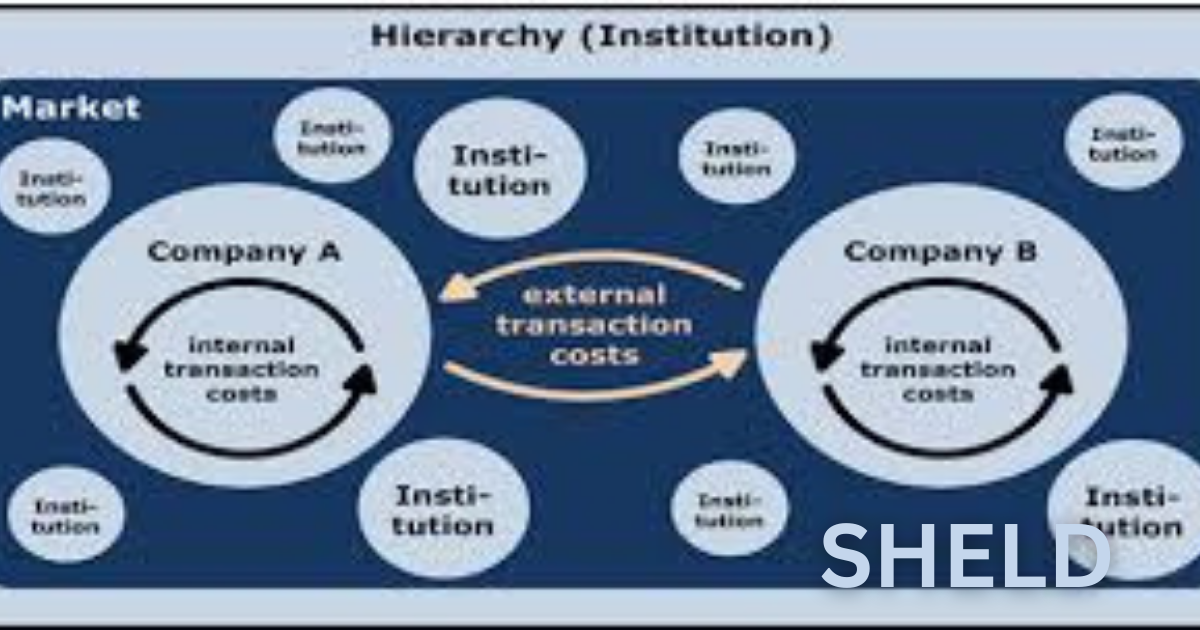

Behavioral effects often vary depending on cultural, institutional, and social contexts. A nudge that works in one jurisdiction may fail in another. - Institutional Capacity

Implementing behavioral policies requires administrative expertise and resources that some legal systems may lack.

Conclusion

Behavioral law and economics enriches our understanding of how legal rules influence behavior by highlighting the limits of rationality. By accounting for cognitive biases, bounded rationality, and heuristics, legal systems can design more effective rules, regulations, and policies. At the same time, integrating behavioral insights raises challenges related to paternalism, unintended effects, and contextual differences.

Ultimately, the future of legal design lies in balancing traditional incentive-based approaches with behavioral insights, creating legal systems that not only promote efficiency but also align with real-world human behavior.