Introduction

The Coase Theorem, first articulated by Nobel laureate Ronald Coase in his landmark 1960 paper “The Problem of Social Cost,” remains one of the most influential ideas in law, economics, and policy-making. At its core, the theorem suggests that if transaction costs are negligible and property rights are clearly defined, private bargaining between parties can lead to efficient resource allocation regardless of the initial distribution of rights. Over time, this simple yet profound idea has spurred heated debates, countless empirical studies, and real-world applications across diverse fields such as environmental economics, corporate governance, intellectual property, and digital markets.

However, as markets evolve and transaction costs take on new forms in the digital age, the Coase Theorem must be revisited and re-examined. How do efficiency and bargaining work in globalized, complex, and highly regulated markets? And to what extent do modern transaction costs—such as information asymmetry, coordination barriers, and digital monopolies—limit the theorem’s practical application?

This article explores these questions by analyzing the enduring relevance of the Coase Theorem, its limitations, and its role in understanding efficiency and transaction costs in today’s interconnected markets.

The Core of the Coase Theorem

The Coase Theorem posits that when transaction costs are zero, externalities—such as pollution or noise—can be resolved efficiently through private negotiation. For example, if a factory emits smoke that affects a neighboring household, and if both parties can negotiate without cost, they can reach a mutually beneficial solution. Whether the household pays the factory to reduce emissions or the factory pays the household for tolerating the smoke, the outcome should be efficient.

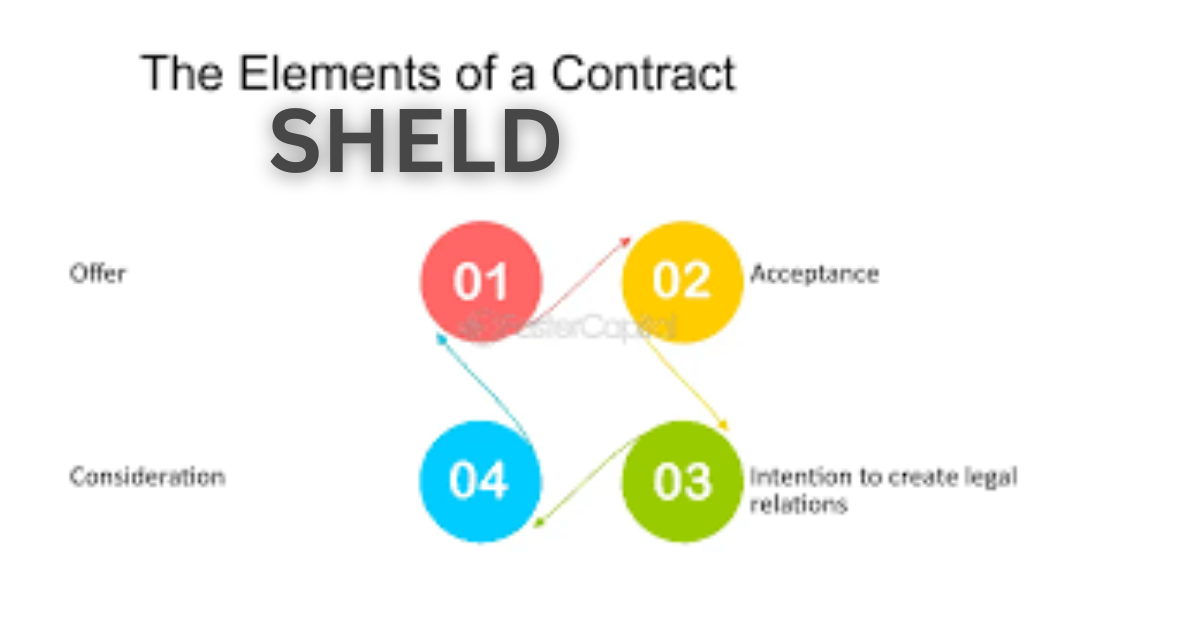

The key assumptions underlying this theorem are:

- Clearly defined property rights – Both parties must know who holds the legal right over the resource in question.

- Zero transaction costs – Bargaining, enforcing agreements, and obtaining information must not incur significant costs.

- Rational actors – Individuals or firms are assumed to act in their own best interest.

In theory, these assumptions lead to Pareto efficiency, where no one can be made better off without making someone else worse off.

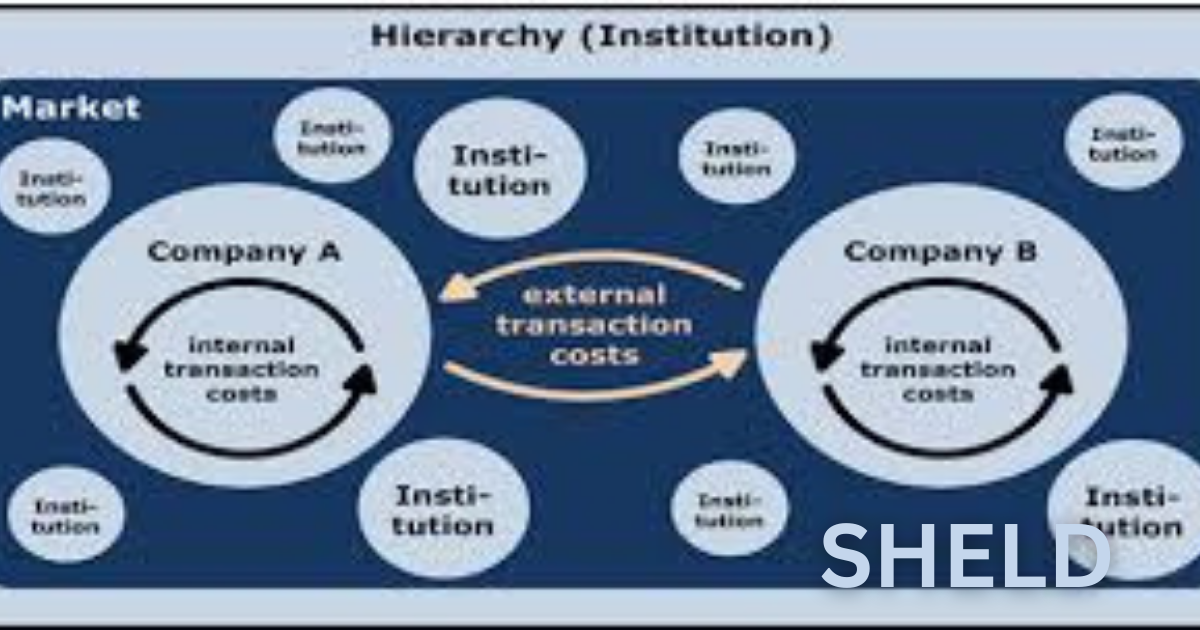

The Problem of Transaction Costs

While the theorem provides an elegant solution in a world without frictions, real-world markets are riddled with transaction costs. Coase himself highlighted this limitation, noting that in most practical cases, high transaction costs prevent efficient bargaining.

Common forms of transaction costs include:

- Search and information costs: Time and resources spent identifying relevant parties and information.

- Bargaining and negotiation costs: Efforts required to reach agreements between multiple stakeholders.

- Enforcement and monitoring costs: Ensuring compliance with agreements.

- Coordination costs: Challenges that arise when externalities affect large groups rather than individuals.

For instance, climate change is often cited as a classic failure of Coasian bargaining. Since pollution affects billions of people across borders, assigning property rights and negotiating global agreements become extremely costly and complex.

Coase Theorem in Modern Markets

- Digital Platforms and Data Rights

In the digital economy, data is one of the most valuable resources. The ownership and control of personal data have sparked debates similar to traditional property rights. Tech giants like Google and Meta derive immense value from user data, while individuals often have little bargaining power to negotiate how their information is used. In theory, if transaction costs were minimal, individuals could negotiate directly with platforms for compensation. In practice, asymmetric information, network effects, and lack of clear rights make efficient outcomes difficult. - Environmental Regulation and Cap-and-Trade Systems

Modern environmental policies often embody Coasean logic. For example, carbon trading systems assign property rights to emit carbon, allowing firms to buy and sell permits. In principle, this creates an efficient allocation of pollution rights. However, the effectiveness of such markets depends heavily on how transaction costs—such as regulatory oversight and enforcement—are managed. - Intellectual Property in Innovation

The protection of intellectual property (IP) rights is another domain where Coasean principles apply. Patent systems aim to define property rights clearly so that innovators can bargain with others. Yet, high litigation costs, patent trolling, and fragmented IP ownership can create “anti-commons” problems, where too many overlapping rights stifle innovation rather than promote efficiency. - Gig Economy and Labor Markets

Platforms like Uber and DoorDash reduce transaction costs by connecting workers and customers directly. However, questions remain about the fairness of these arrangements, given power imbalances, algorithmic opacity, and limited bargaining rights for workers. Here, the Coase Theorem collides with modern labor realities.

Efficiency vs. Equity

One of the main criticisms of the Coase Theorem is that it prioritizes efficiency over equity. While private bargaining might lead to efficient outcomes, it does not guarantee fairness in the distribution of wealth and rights. For example, if a wealthy polluter pays a poor community to accept environmental harm, the outcome may be efficient but socially unjust. Modern policymakers therefore face the challenge of balancing efficiency with distributive justice.

Transaction Costs in the Digital Era

In contemporary markets, transaction costs are often less about physical negotiation and more about informational and structural barriers. These include:

- Information asymmetry: One party, such as a digital platform, often knows far more than the user.

- Network effects: The dominance of a few firms creates monopolistic structures that hinder bargaining.

- Algorithmic opacity: The complexity of digital systems makes it hard for individuals to evaluate trade-offs.

For example, when users click “I Agree” on privacy policies, they are effectively relinquishing rights without true negotiation. Theoretically, Coase would argue that bargaining should solve these problems, but the transaction costs of reading, understanding, and negotiating terms with massive corporations are insurmountable.

Policy Implications

Revisiting the Coase Theorem highlights the importance of institutions in reducing transaction costs and enabling efficient outcomes. Governments and regulators often step in to lower barriers to bargaining, assign rights, or enforce agreements. Examples include:

- Environmental regulations: Cap-and-trade, carbon taxes, and emission standards.

- Data protection laws: GDPR and other privacy regulations that establish user rights.

- Antitrust enforcement: Preventing monopolies that distort bargaining.

- Collective bargaining frameworks: Empowering labor unions to negotiate on behalf of individuals.

Thus, while the Coase Theorem is a powerful analytical tool, its practical relevance depends heavily on the institutional context.

Conclusion

The Coase Theorem remains a cornerstone of economic thought, but its idealized assumptions rarely hold in today’s complex markets. Transaction costs—whether in environmental policy, digital economies, or intellectual property rights—are ever-present and often prohibitive. Modern markets reveal that efficiency alone is not enough; equity, fairness, and institutional frameworks are equally critical.

By revisiting Coase’s insights in light of contemporary challenges, we gain a richer understanding of how efficiency and transaction costs shape modern markets. Ultimately, the theorem’s greatest contribution may not be its assertion that bargaining always leads to efficiency, but rather its invitation to analyze where transaction costs arise, how they distort outcomes, and what institutions can do to address them.